“Each day the traders are kidnapping our people … This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated.”

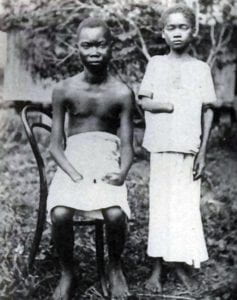

“Twa Mwe, a Kwango chief. Indigenous leaders often faced the choice of supplying their people as rubber slaves or being held hostage or killed.”

“See! … I always have to cut off the right hands of those we kill in order to show the State how many we have killed.”

“ … sometimes shot everyone in sight, so that nearby villages would get the message.”

“ … for if the natives hide, they will not go far from their village and must come to look for food … When you feel you have enough captives, you should choose among them …”

Where has everybody gone?

Mama.

Papa.

They could not have crossed the river’s mouth

Nor could have set foot into the night

It was all here yesterday..

But what has happened to yesterday?

Oh, they must be hiding surely

Behind the door!

No?

Or in the wheat hut

No.

If not this corner, then the next..

But there is nothing to be found

You had promised me infinity

But I am left bewildered, soulless

There is only fear

For you must have gone with the wind surely

(Where else but the wind?)

Not but a tear

For as the hour grows near, darkness descends

And so I remain

I remain wondering

They will return soon

Just another night…

In quarantine, I’ve been trying to read more, getting my mind off things and perhaps learning more about this strange world around me. I happened to stumble upon a book about the Congo and central Africa, something that I had never really learnt about, but I was still interested. This poem was inspired by the novel, King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild, which is where these quotes originate from.

This text is a nonfiction, which is exactly why I chose to read it as stories of history and historical events are something that I had never been quite fond of and is evidently reflected in any assessments that revolve around non fiction. But this story was something totally different, a work of history that, as one critic puts, “reads like a novel.”

King Leopold’s control over the Congo in central Africa, and the horror that soon ensued is what I consider as a ‘hidden holocaust’, something that seems to have never been put on par with the horror and destruction created by something like the Nazis in Europe. It is most definitely a tale that needs to be more widely heard and understood, and this novel was really one of the first pieces of nonfiction that I have read that has opened my eyes to something so dramatic and severe that seemingly has never been discussed nearly as much as it should be. The personal accounts, reports, and photographs felt unmatched with any other book that I have read, and so I wrote this poem in an attempt to capture those emotions and feelings from the perspective of someone caught up in all of this, in the view of a child. As mentioned in the novel, the Indigenous peoples and their European conquerors were two totally different societies, each with their own respective opinions and values. As a result, the people of central Africa were battling against an unexpected and unnamed enemy, controlled by sheer fear and firepower. I wrote this poem in an attempt to capture these feelings and emotions, from somebody who has been able to elude the horror, and is able to tell the tale.

The first stanza was written to enforce the idea of a speaker, being a young child. Villages were often raided and hostages were taken in order to gather more workers for rubber harvesting, which soon developed into a lucrative business for King Leopold of Belgium. She has been one of the few who has managed to pass through the horror, albeit unknowingly. This particular voice had been chosen in order to develop a more innocent, naive tone, one that does not quite understand everything that is going on around them and does not have much power to be doing anything about it. They wonder what has happened, but being the imaginative, innocent mind that they are, will come to their own conclusion, as it is really the only idea left. It could not be possible for an entire village, an entire society to be swept clean in just one night. No, it must be something else. And yet, for 23 silent years, this is exactly what had happened. There was nowhere left to go, nothing to hold on to, and as one is left to their own imagination, they will subsequently end up with their own interpretation.

The second stanza further delves into the first with more reasoning and questioning, “For you must have gone with the wind surely”. These questions are still left unanswered, as the speaker begins to further wonder and criticize. All of these promises, all of this trust, has gone to the wind, what else could have taken you ‘but the wind’? As time goes by, flies, and as the day ends, there is nothing else to feel but fear, confusion.

Lastly, the poem ends with hope, a trust that, although can be damaged, will never leave. This faith remains, and so does the speaker, guided by the blind faith that will inevitably control. After all, what else is there to possibly do in a world that has been silent perpetually, and will demonstrate no need to make a change about it.