The worst feeling is not feeling.

Not anger. Not guilt. Not even vengeance, which can consume your entire being, thoughts and all. Because when you experience any other emotion, at least you feel something. You feel human— alive, and full of feeling— and when you have feeling, you have hopes. Dreams. But when your senses are numbed, and your head is blank, and you just exist for the sake of existing, are you even living? Or are you no different than an empty corpse wandering the Earth; waiting to be free, or to be dead, or both?

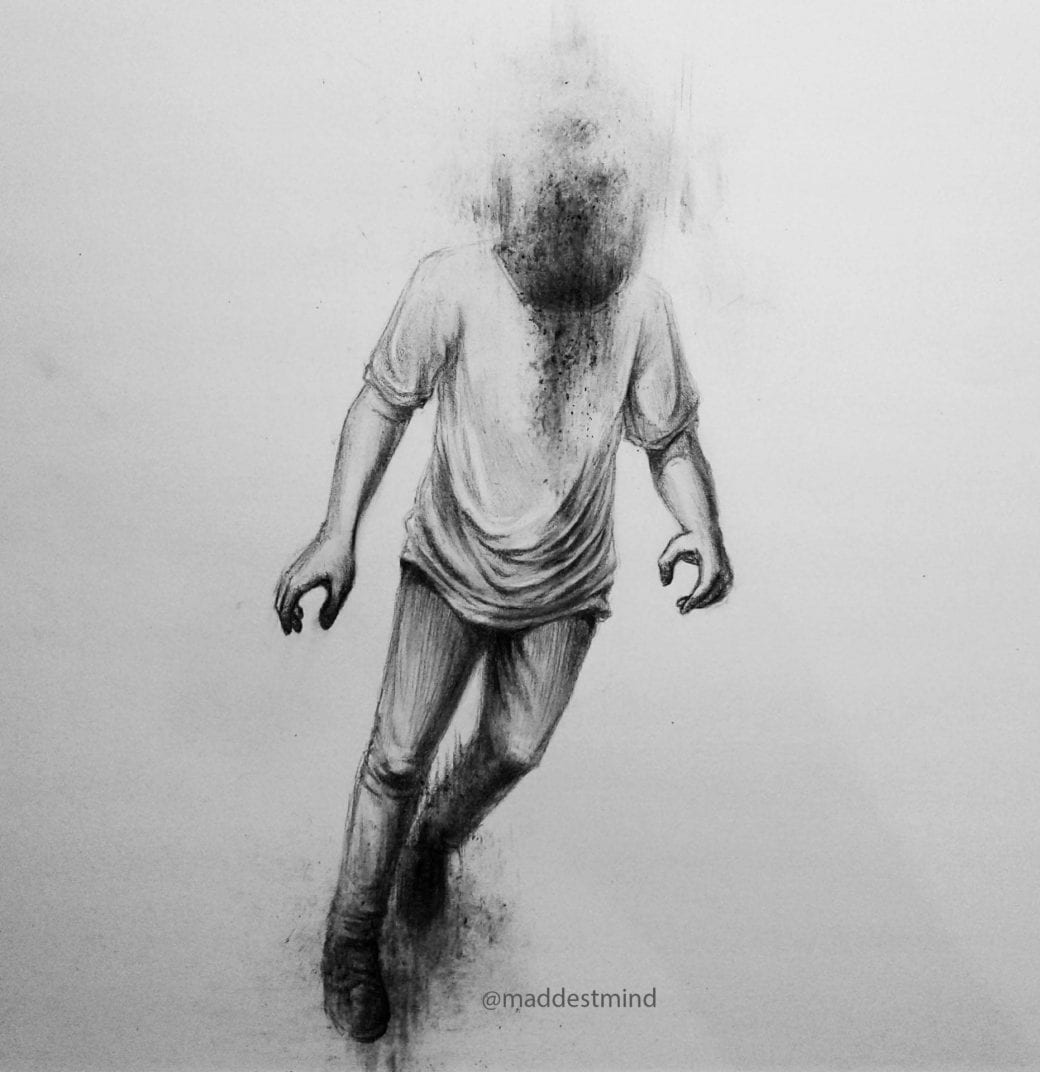

The word “corpse” was repeated throughout Night. At first, I did not pay much attention to it. It was just another word, another description. That was, until I read this line: “From the depths of the mirror, a corpse was contemplating me.” (115) This was after Elie was liberated from Buchenwald and transferred to a hospital as a result of some kind of poisoning. He had survived. But why did he see himself as a corpse when he was still living? The word “corpse” simply means “a dead body,” did it not? Perplexed and fascinated, I read it again and again. Then, it hit me. I watched the process unfold. I watched the Nazis, the oppressors, gradually strip away pieces of their prisoners— their families, their beliefs, their memories— and burn them to ashes. They no longer had anything to hold on to. I watched them ruthlessly crush their bright futures as they stood in rows helplessly. Hopelessly. And I watched Elie slowly lose his senses one by one, until he was left with nothing but the shell that he called a body.

He became a corpse.

A corpse with no sense of taste. His first ration of soup he did not touch; his third he devoured. It did not matter what kind of soup he had, or how stale the bread was. All that mattered was that he ate. “The bread, the soup— those were my entire life. I was nothing but a body.” (52) Elie was so starved that he ate grass and potato peels found on the ground— things one would not consider food. He didn’t either. It was like fueling a car with gas; it was the only thing keeping him running.

A corpse with no sense of touch. He once was capable of feeling pain and fatigue. But when excess amounts were inflicted upon him, he did not feel it anymore— his body got used to it. “My wounded foot no longer hurt, probably frozen… It had become detached from me like a wheel fallen off a car.” (92) Elie compared his body to a car; his leg, a wheel. He saw his body as a separate part from him, one that bore no emotional connection; one that served as a vessel. And once upon a time, that vessel held thoughts and emotions, and so it resembled a human of sorts. As time passed and his thoughts and emotions decayed, the vessel became empty. It was like a hollow corpse; it was the only thing he had left.

A corpse with no sense of smell. He had arrived at Birkenau to the smell of burning flesh. When he arrived at Buchenwald, he did not notice it. “Very close to us stood the tall chimney of the crematorium’s furnace. It no longer impressed us. It barely drew our attention.” (104) Being constantly engulfed with the stench of burning and rotting bodies had made Elie indifferent to the unpleasant scent. It was like the stench of death haunted him; it was the only thing he knew the smell of.

A corpse with no sense of sight. Despite spending every day with his father, he did not know who he was as much as he thought he did. “He looked at me for a moment and his gaze was disant, other-worldly, the face of a stranger.” (108) If this was a brief and insignificant mistake, Elie wouldn’t have kept it in his shortened book, much less remember it. But he did. He had mistaken another prisoner for his father. After all, they all wore the same striped clothing and the same blank expression. It was like there were only two groups of people: the SS and the prisoners; it was the only thing he recognized.

A corpse with no sense of sound. It came to a point where he could not distinguish between the voices of his friends. “You’re crushing me… have mercy!… The same faint voice, the same cry I had heard somewhere before. This voice had spoken to me one day. When? Years ago? No, it must have been in camp.” (93) The voice had belonged to Juliek, but it took Elie a long time to figure it out. Very rarely did he hear human words, especially ones begging for mercy. Most of the prisoners died silently. It was like he lived in silence; it was the only thing he heard.

A corpse with no emotion. It started out small. It was caring a little less; reacting a little slower. “I stood petrified. What had  happened to me? My father had just been struck, in front of me, and I had not even blinked.” (39) Elie had arrived at Auschwitz the night before, yet he had already picked up on the “every man for himself” mindset that every other prisoner developed. His instincts had protected him from the possible harm, but at what cost? Throughout the novel, similar scenes reoccurred over and over, like a broken cassette, winding and rewinding. Each time, the pause between his frozen body and his racing thoughts grew. And then, the death of his father. “Eliezer” was his last word, and he did not move. By then, it was no longer just fear that was holding him back— it was habit. Habit, and his dulled emotions. Because in order to survive in a place full of death and suffering, he had to detach from them. Were it not for his numb mind, he could have ended up like Meir Katz, who broke down after becoming overwhelmed with emotion; therefore, it was necessary to suppress them. He could not afford to feel, not when any one of his friends could die at any moment. His father had died. He did not cry— he could not cry— he was out of tears. It pained him, but what could he do? He had forgotten how to cry, how to show emotion, how to feel. And somehow, that was worse than feeling.

happened to me? My father had just been struck, in front of me, and I had not even blinked.” (39) Elie had arrived at Auschwitz the night before, yet he had already picked up on the “every man for himself” mindset that every other prisoner developed. His instincts had protected him from the possible harm, but at what cost? Throughout the novel, similar scenes reoccurred over and over, like a broken cassette, winding and rewinding. Each time, the pause between his frozen body and his racing thoughts grew. And then, the death of his father. “Eliezer” was his last word, and he did not move. By then, it was no longer just fear that was holding him back— it was habit. Habit, and his dulled emotions. Because in order to survive in a place full of death and suffering, he had to detach from them. Were it not for his numb mind, he could have ended up like Meir Katz, who broke down after becoming overwhelmed with emotion; therefore, it was necessary to suppress them. He could not afford to feel, not when any one of his friends could die at any moment. His father had died. He did not cry— he could not cry— he was out of tears. It pained him, but what could he do? He had forgotten how to cry, how to show emotion, how to feel. And somehow, that was worse than feeling.

The final chapter reflected that— it was monotonous and brief, unlike the rest. Even though it was eventful and significant, it did not feel that way. It felt empty. There were no hopes. No questions. In the beginning, Moishe the Beadle explained “…every question possessed a power that was lost in the answer… Man comes closer to God through the questions he asks Him… The real answers, Eliezer, you will find only within yourself.” (5) At the end, Elie looks into the mirror. He sees a corpse…

The worst feeling is not feeling.

While contemplating how I was to go about writing my response, I came up with a small poem describing Elie’s journey of “not feeling.” I then expanded on it to write the piece above. Enjoy :))

i no longer taste what i eat

(as long as i am eating)

not a gaze nor a smile

could make me feel the beating

to die now or die later

what did it matter

for they crushed my dreams

and i watched them shatter

i no longer feel anything

neither pity nor sorrow

i no longer have hope

no hope for tomorrow

i deleted my memories

buried my past

that night they had taken my father from me

and i was free at last!

Featured Image Credits: https://www.reddit.com/r/drawing/comments/8g7yy5/hollow_graphite_and_charcoal_pencils_on_paper/

(I am pretty sure the artist is @glenntejano.art on Instagram.)

Image: https://www.123rf.com/clipart-vector/doodle_path.html?sti=ldvemnbsbiiwpsm84d|

Dear Tiffany,

Wow! I was just totally not expecting the thoughts and emotions that came out of this piece, and it was quite a ride reading through everything you had to say, especially the poem at the end. I love the way that the quotes you chose to use were just woven into the rest of your writing, all of it flowing extremely smoothly. You did an amazing job combining your own thoughts about Night with what quotes and evidence there was from the memoir, and it all just felt like one big story that was meticulously crafted to perfection. I feel that this is now one of my favourite lines that I have read on this blog: “It was like he lived in silence; it was the only thing he heard.”

As for improvements, it took me some time to actually find anything that could be improved upon, but I would say that you could perhaps be a bit more mindful of your usage of those short, brief sentences. It seemed to me that you liked to use a lot of those. But once again, this was only a minor issue, and I found that it did not take away from the quality of this piece much at all.

I really enjoyed reading every bit of what you have written here, and I’m extremely glad that you have taken the time to write out all of your thoughts and feelings about Night into this post, along with the poem at the end. I can tell you have put lots of effort into this piece, and I personally feel that I have learnt a lot which I can incorporate into my own writing in order to improve.

Sincerely,

Ekaum